Birth: 13th February 1866 (1272 Bengali year, 1 –Falgun, Monday, Morning-7.30AM, On the day of Shiva Ratri

Birth Place: Khalisamari, Mathabhanga, Coochbehar state

Father: Shri Khoshal Sarkar

In this article several parameters have been highlighted regarding Raisaheb Panchanan Barma’s biography or life history and Kshatriya movement. Why it was needed, how things done excluding myths and social status of majority Koch Rajbanshis after kshatriyanisation. How intra conflict happened within classes from economic point of view and what other people thought about koch rajbanshis even after achievement of Kshatriya status etc. He tried to incorporate Kshatriya spirit to his people not just wearing sacred thread or nogun / poita that reflected in his poem Dangdhori Mao.

Mother: Champala Debi

Raisaheb Panchanan Barma of Coochbehar and Rajbanshi Kshatriya movement

Contents:

1. Social Status and Kshatriya Movement

2. Raisaheb Panchanan Barma on Kshetranath Singh’s pen

3. Structure of Kshatriya Samiti

4. Dangdhori Mao

5. Kshatriya Sangeet by Govinda Chandra Roy

6. Kshatriya Samiti’s Proposals

7. Expel from Coochbehar State

8. Last Breath of Panchanan Barma

9. Tebhaga Movement and Kshatriya Samiti [Post Panchanan Era]

10. Government’s eye on Rai Saheb

Social Status and Kshatriya Movement

In the social hierarchy of British Bengal, the aboriginal Rajbanshi (earlier Koch, although Coochbehar state or Kamta state dynasty was Koch dynasty or Koch kingdom) were placed at the bottom of the structure (who was that almighty that placed people at bottom of social structure? It was nothing but to take authority & power in hand at any cost by so called upper caste), along with the Namasudras, the Pods and the other Antyaja castes. Those among them, who were relatively more advanced, economically and educationally, were not ready to bear this lower caste stigma anymore and therefore argued and appealed in favour of their Kshatriya status. Majority of Koch got affidavit as Rajbanshi in broad sense and sections of Pods also renamed as Rajbanshi which created a cultural conflicts among newly developed Rajbanshis. Koch oriented Rajbanshis had distinct language (Rajbanshi/Kamtapuri language, culture what generally found in kamta literature. But other sections such as Pods, Namasudras, Tiors who renamed as Rajbanshi did not ready to adopt language and culture. They renamed their caste nomenclature for Kshatriya statuts only. They know only Raisaheb Panchanan Barma not Panchanan Barma’s language, culture and traditional customs.

Raisaheb Panchanan Barma / Khalisamari Campus

The social and economical situation also provided a sufficient ground for the Rajbanshi’s assertion of a Kshatriya identity and their endeavour to build upper caste solidarity. The gradual settlement of upper caste Hindu gentry in what were traditionally the Rajbansi dominated areas of north Bengal, the existing balance in local power structure had changed. The immigrant so called upper caste gentry in course of time had become comparatively more dominant group in local society, economy and politics. They managed the local administration and by virtue of their closeness to the administrative power and their intelligence, they emerged as the dominant landholding class. As they were socially guided by the traditional Brahmanical cultural values, the Rajbanshis, who had a tradition and culture of their own, failed to get a respectable position in the status estimation of these immigrant so called upper caste gentry.

There were sharp dissimilarities between the cultural practices of these two groups and the upper caste gentry behaved in a rather proudly way with the local Rajbanshis and treated them as ‘backward, uncultured and even Antaja (For Readers/Viewers: Every one keep in mind thinking is comparative in nature, good and bad words are always comparative should judge on the basis of bench mark, Rajbanshis have rich cultural background but they were uncultured on Bengali gentry point of view. They are also uncultured/unmatched from Rajbanshi point of view. Important things are, own economy-education-administration-political backbone).

They used to refer to the Rajbansis as “Bahe”, implying their cultural inferiority. The word Bahe was a distortion of the word “Baba he”, by which the Koch Rajbansis generally used to address a person. On the contrary Koch Rajbanshis used to refer to the outsiders as “Bhatia”, meaning an outsider (came from Bhati place) to their land. Thus, the attitude of cultural superiority of the immigrant upper caste Hindus and their general tendency to look down upon the Rajbanshis created a psychological barrier that prevented a closer relationship between them and the latter. This detachment behaviour from the caste hindus might be indirectly promote caste solidarity among the Koch Rajbanshis. So its a uncivilized characteristic downfall of so called self claimed upper caste people not aboriginal koch rajbanshi or other aboriginal tribes.

"I hate to use a toga used by a “Rajbanshi”–Advocate Maitra (Rangpur Court, 1st decade of 20th Century)"

Rangpur Court, sometime in the first decade of the twentieth century. Raisaheb Panchanan Barma used his toga in a hurry, he had to hear this from Ukil Maitra while returning it). Ukil Maitra was a Bengali – in language, culture.

In another incidence of caste hatred, Upendra Nath Barman (immediate follower of Raisaheb Panchanan Barma) mentioned that one day a Rajbanshi student, staying in Rangpur Normal School boarding house, had entered the kitchen of the hostel to enquire from the cook, whether the food was ready or not. But on this plea two or three boys, belonging to the so called higher castes, refused to accept that food, which ultimately had to be thrown away for the consumption of the cows and fresh food had to be prepared.

Panchanan Barma’s home / Khalisamari

Upendra Nath Barman in his autobiography has narrated another such experience from his own student days at the Cooch Behar Victoria College (presently A.B.N Seal college) during 1916-20. In the college hostel there were two dining halls and students took food in either of these halls according to their individual likings. But one day the hostel superintendent in a notice declared that one hall would be reserved for the Brahmans, and the other for the Kayasthas, while a separate arrangement would be made for the students of the other communities for taking their food. Upendra Nath protested against this caste discrimination by the hostel superintendent and complained to the state administration. Ultimately the matter was brought to the notice of the college principal, who made it clear to the hostel superintendent that “Victoria college hostel is not for those who observe caste distinction” . This was in fact His first bitter personal experience of casteism.

Another incidence, in Rajshahi college hostel a Rajbongshi student who was not allowed to enter the dining hall, was ultimately compelled to have his meal in the hostel courtyard. Furthermore, the students of the so called lower castes were required to wash their own utensils.

Raisaheb Panchanan Barma on Kshetranath Singh’s pen

The late Kshetranath Singh of Rangpur (BL, MLA) described in his book “Biography of Raisaheb Panchanan Burma” (in 27th June 1939) – a few lines from that book trying to expose – “Oh brother Kshatriya, where do we go now? The country that we used to know as the green land of our nation, the kings that we considered as our national pride and the archeological sites like Kamrup, Gosanimari, Bhavchandra’s Paat/Garh, Gopichand and Mainamati’s Garh, Bhim’s jungle, etc. All historical antiquities or places are being occupied gradually, but we are indifferent. We saw Panchanan Barma for his desire to save those antiquities. Can’t we hope that the Kshatriya youth will voluntarily take up the task of completing his unfinished work in the future? “

Sh. Kshetranath Singh also wrote that we have laziness and apathy. His observations are not to be denied as well. He wrote, “The misfortune of our nation is that our laziness and indifference have made us beggars of foreigners, even though there are many things to write and research about North Bengal and our Kshatriya nation and save the culture.”

At the time when Rai Saheb Panchanan Burma was educated in a remote village and later moved out of his home to pursue higher studies, the state of education system was very poor. English education had not yet spread to the state of Cooch Behar. However, Maharaja Nripendra narayana was making great efforts to educate the people of Coochbehar and neighbour area in English education.

Thakur Panchanan Barma passed Entrance examination from Cooch Behar, later I.A and B.A also Passed. Then with so many difficulties he passed M.A from Calcutta with efficiency. Even after passing this, he could not get a good job in his native place and took the post of boarding superintendent at Cooch Behar College and Boarding with a small salary. He applied for Nayeb Ahilkar post to Dewan Kalikadas Dutt but Dewan rejected Panchanan Barma’s application for his extremely anti-Cooch Behari attitude. He not only rejected the application but spreaded hatred against Panchanan Barma to expel from Coochbehar state. But I don’t think that’s the case. The seeds of hatred that Dewan Kalikadas Dutt sowed became a mammoth tree in time! Indigenous (Aboriginals) people need to be understood who are actually fostering a hostile attitude yet. And the enemy should never think of as weak, no matter how weak he seems from the outside.

Raisaheb Panchanan Barma came to Rangpur from Cooch Behar in 1901 and started practicing law. If he got the job of Ahilkar in Coochbehar state, Koch Rajbangshi society would have remained in the unidirection, Panchanan Barma would not have become Thakur Panchanan Barma.

Sh. Kshetranath Singh, while writing the history of the Rajbongshi Caste, mentioned the names of Raja Kanteshwar, Vir Chila Roy, Maharaja Naranarayan and other Koch Kings. “Chila Ray with his powerful dynamic army defeated the Gaur king Hussain Shah with indomitable might, destroyed the city of Gaur and forced the king to kneel and apologize.” We all know that Koch Raja Naranarayana’s brother and commander was Vir Chilaray. But even though we live in this modern age of social media, we create divisions with Koch and Rajbanshi and waste time arguing unnecessarily, which an expression of lack of knowledge and generosity.

Even before Thakur Panchanan Barma left for Rangpur in 1901, Babu Harmohan Khajanchi started the Kshatriya movement, demanded that the word “Kshatriya” should be written in the census report. The first session of the Kshatriya Samiti began on 18th Baishakh, Sunday, 1317 (Bengali year) at Rangpur Natyamandir. About 400 people gathered at that session.

Structure of Kshatriya Samiti

To reach the mass of the Rajbanshi people, and spread over a number of districts, the Khatriya Samiti set up an organizational network –

Mahamandali (in each subdivision),

Mandali (consisting of one, two, or more village) and

Autarmandali (consisting of some ‘paras’ or taris).

The village units are as followed- Mandali was at the top and Patti was at the bottom. Ten or twelve Pattis formed one Gadiani and five to seven Gadianis formed Ghata. In each, Patti there was a Pramanick. The Gadians of five to seven Gadianis and the Pramanicks formed a Ghata or Mandali.

The working committee of every Mandali was comprised of active and young social workers. The mandalis had to introduce socio- religious reforms within the community, to supervise its various social programmes and to convince the common people to accept social practices representing their kshatriya status. All members are directly answerable to the central committee of the Kshatirya Samiti located at Rangpur. The Samiti appointed many preachers or procharakas including Maithili and Kamrupi Brahmin to carry on the movement down to village level. By 1926, three hundred Mandali samiti had been established.

Panchanan Barma made a proposal in the 13th annual conference of the Kshatriya Samiti for the formation of volunteer groups with proper training in every village Mandali to save women from hooligans. This proposal was accepted overwhelmingly. Therefore, to awaken the Kshatriya spirit in order to protect women, Panchanan Barma wrote in Kamtapuri language, a rather inflammatory poem, titled “Dangdhori Mao” (mother, with the power to protect).

Dangdhori Mao - Thakur Panchanan Barma

Chomki uthil dukrun shuni Dangdhori mor mao,

Disha duor naai, khali kollohar, dakhe songsarer bhao।।

Baap bhai er ghor, soamir kola aar jeite nari thaake।

Jor koria nuccha gunda nia jaiteche take।

Bera bhangia, soamik maria, bon jhiok dhaakke thuia।

Poi dhore naari, taako bhangi nigai, mukhot kapor dia।।

Hia fata taar atran uthe seona kapor chedi।

Dukrun taar teo shuna jai akash batash bhedi।।

Beta chaoa gula joro hoya, khaali, fal fal kori chai।

Dangdhori mao kordhe hakia, gaain dhoria dhaai।।

Dangdhori Mao (Beta chaoar proti / For youths)

‘Chhiko chhiko’ re mora beta chaoa, dhik dhik tore dhik।

Mao boinok tor nuccha nigai, tengo thaakis tui thik?

Morod morod koulais khaali kemon tor mordani?

Pathar bari haate aasi khali, maiar agot kerdaani।

Laaj naai tor, hiao naai tor, bol naai tor dhore।

Ei baade tok tepo bou chiko chiko kore।।

Patani pinda beta chaoa tepo bou, toke koiche,

Bhul koria tepo bou tok beta chaoa maniche?

Eito haamera beti chaoa, hamaro hiao bhal।

Aasuk nuccha narer beta, gaain dia tulim chhaal।।

Dhorom rakhimo, korom rakhimo, rakhimo baap bhaaier maan।

Apon kuler gourab rakhimo, katimo nucchar kaan।।

Dao ache tor, kural ache tor, haate ache tor naati।

Baati kata holongoch ache, goru chora penti।।

Shaaler shiri baha duikhaan, shilhen buk pata,

Teo tor mao boinok nigai, nuccha gunda beta।

Shunish na ki, kaande mao tor, maari hapran

Nuccha gundai nia jai mok, tor ki re naai kaan?

Haat kire tor kuria naga, tui kire chakula?

Buker bhitor hia naai tor, khali kharer pala?

Jool jool kori chaya achis, jeno momer putula?

Thor thor kori kapir nagchis, jeno gohili ola?

Kemon kori tui achis thik, naai kire buker pata?

Mao boinok tor pore hore, tui kire notir beta?

Uai kire tor jononi nomai, nomai apon boin?

Chhiko chhiko re, tor mao ki tok naai dei giyan?

Imai jonmiche imar petot, umai umar petot dhora?

Jononi mane nari sobbai, tui kire bhui fora?

Jonom kire tor chagoler petot, naai mao boin bhao?

Mao boinok tor pore hore, kordhe jole na gao?

Khaali mokoddomai dusta domone ferena, firena dhorom maan।

Bhangi nucchar haar; mao boinok rokkha, baaper betar kaam।।

Mao boinok Jodi rakhir naa paris apon bahubole।

Khali paaper bojha boichilo mao tor, ei dosha tar fole।।

Mor mor tui elai mor, norokeo tor naai than,

Mao dhortir bojha komuk, jurauk soti mar poran ।।

Dangdhori Mao (Kshatriyor proti / For Kshatriyas)

Ai ai re kshatriyagula, tomak dako barong bar।

Tomar kaan naai ki, ontor naai ki, kandon shunibar?

Houk naa kane dur durantor, porbot nodi maajhe।

Kshatriya Jodi thik hois tui, tengo shunbu kaache।

Atura kandon, kshatriya kaane, apne aasi nage।

Hidde uthe hurka tufan, shorire shakti jaage।।

Tilek deri aar soina, begi hoyre khara।

Ostor naa paai, baha dhori dhaai, choukhe aguner dhara।

Kordho dekhi dusta dushman poth chhari dei aage।

Thauk pori tor nuccha gunda, doityo danab bhage।।

Pao er bhore pahar bhange, firia naa chai bir।

Dustak mari, artok tari, tobe hoi se thir।

Hindu musalman bichar nai re, manus jontu to noi bhin।

Ulsi dhaya artok uddhar, ei kshatriyer chin।।

Bipod jhonjha joto-e aise toto-e ulse chit।

Apon bole bipod domai, ar gai ister geet।

Kshatriya koholais, poitao jhulais, boro boro tor kotha।

Thik hoi shun bujhia dekhi, tuie kire kshatriyer beta?

Tui kire kshatriyer beta, tare bijer dhara।

Tare nou ki boi shirai tor, tare tejote bhora?

Tui kire sei kshatriyer beta, jaar hiai otut bol,

Tare bhab ki buk bhori tor nachai dehar kol?

Tui kire sei kshatriyer beta, jar rokksha dhoromer bhao।

Artok dekhi ar chinta nai, chetia uthe gao?

Tui kire sei kshatriyer beta, tej uchli pora।

Na paai ostor baha dhori dhai pathor kore gura?

Tui kire sei kshatriyer beta, tui kire sei bir।

Dustak mari artok tari, tobe je hoi thir?

Tui kire sei kshatriyer beta, sahos uddome bhora।

Juddher kothai jhappi agai, shotruk bhabi mora?

Tomak dekho keno morar moton, jiu nai jon ghote।

Kshatriya bhaber kotha shuniao jiu cheti naa uthe।

Kene re tomra udash mone etti utti chao।

Kshatriya bhaber kotha shuniao kosh koshai na gao?

Kene re tomra manji mora ros pao nai ki mule।

Baap mao ki tej jogai nai, kshatriya noai kule?

Kene re tomra shelshela pora, teje deha noi bhora।

Tiri loker por julum shunile, gorji na hou khara।

Shun pottiran oi je narike nia jaiteche age।

Jaak dekhile kshatriya prane barude agun lage।।

Tengo kene tor kordho jolena, forki uthe na gao।

Kshatriya teje jonmo nomai, kshatriya nomai tor mao।

Kshatriya koholais, kshatriya nemais, nai kshatriyer kaam।

Kshatriya rokto nai shorire tor, char kshatriya naam।।

Kshatriya naamta shakti somudai bhogobano jaak chai।

Sei naamer ei dosha dekhia hiya fatia jai।

Kshatriya na hoi shelshela pora, teje deho taar bhora।

Tiri loker por julum shunile gorjia hoi khara।

Jila Rangpur, thana Mithapukur, Bhagabatipur gaon।

Dhoinno buker pata, kshatriya beta, Kuranu taar nao (name) ।।

Pata nelai apon dhione, Kuranu apon kshete।

Aoja poril kanot bapre, agaore rakho moke।

Chomki uthil bir Kuranu kordhe chharil haak।

Kon shalare? Thakis khanek? Ki kois mor maak?

Dhai munsi poran fati shishya parar mukhe।

Murshid kande shuni shakred jhukil jhake jhake।

Patanela taat, kordhe Kuranu, ghare dhoril take।।

Harbhanga maar maril Kuranu, kaar baape aar rakhe।।

Thosh nagi geil shishyagulak, dekhil paaper fol।

Disha na pai aar mone mone bhabe, ‘uh! eitar ki bol’।।

Kordhe aise sokha Kinaram Kuranur pache pache।

Tako naa jane bir Kuranu kaam saril nije।

Dhoinno Kuranu tui je kshatriya, dhoinno tor baap mao।

Nij montro thik Bhabani pujilu, haase dhorti mao।।

Govinda Chandra Roy’s kshatriya Sangeet -

“Mora chahina artha, chahina man,

Chahina bidya, chahina jnan,

Mora chahi shudhu jatir pratistha,

Mora chahi shudhu jatir pran”.

[We do not want money, nor do we want prestige, We do not want education, nor do we want knowledge, We only want the recognition of our caste, We only want our caste to be alive]

Although it was a song/poem to create caste sentiments among Rajbanshis during gatherings for establishment of word ‘Kshatriya’ and ‘Rajbanshi’ anyhow. But what common people or uneducated and economically poor peasants got message out of these four lines? Can you imagine? Its total contradictory and obviously raise question on objectives of Kshatriya Movement what i feel. It reflects that some economically established people of feudal society tried to organise kshatriya movement for their own benefit only. For their own benefit they tried to aggregate the masses.

During the Kshatriya movement, one of the five proposals was the second one – that is caste Rajbongshi and Koch, two separate castes, to inform the government.

The name “Koch caste” was established at that time. In other words, the word Koch was already written by the government or ethnologists. The word Rajbongshi is a new creation in that sense. If the language and culture of Koch and Rajbangshi same, then what goes with the name or nomenclature? Moreover, there was a caste called “Tior caste”, the people who lived in South Bengal. At that time, it is difficult to say whether it was possible for some Kshatriya movement individuals to have connection with Tior caste.

Kshatriya Samiti’s Proposals

Panchanan Barma’s letter to chief secretary of Bengal Government on behalf of Kshatriya Samiti. It was a formal letter to give information about activities of Kshatriya Samiti, social and economical condition of kshatriya people and to take care of interests of entire kshatriya society.

"To

The Chief Secretary to the Government of Bengal.

Sir,

I as Secretary of the Kshatriya Samiti most respectfully beg to make the following submissions for favour of being placed for consideration of the Secretary of State for India to whom we beg to offer our heartiest well come to India, and humbly beg to be graciously permitted to send a deputation to wait upon the Secretary of the State.

1.That the Kshatriya Samiti is an association representing about 22 Lakhs of souls belonging to Kshatriya Community, inhabiting the districts of Rangpur, Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri, and other neighbouring districts and the State of Cooch Behar.

2. That the people though now in a somewhat backward state in point of education and progress are the Successors of a great people who founded great Empires and otherwise played great parts in the part history of India.

3. That the association is non-political and aims at the intellectual, social, moral and religious progress of the Community, and final emancipation of the souls by the finding of the great soul in all we see, is the goal.

4. That for the realisation of that goal gradual expansion of the individual soul is necessary which can only be attained by living in Samajas or Societies organised with a view to that goal and protected by the Sovereign power of the country which of yore used to belong to the country and the controlling head to be a countryman with identical thoughts and feelings.

5. That as a part of the great Hindu Community, this Kshatriya Community enjoyed the self-improving social organisations, but owing to misfortune that fell upon them a few centuries back and specially the present system of education, that organisation which used to secure

obedience to superiors, love to all, love and respect to the parents and superiors, reverence to the good and beautiful, as also peace and prosperity to all, has been greatly damaged and there are apprehensions of tendencies appearing in not far distant future of discontent and even of disrespect to law and order of the country which is being viewed with alarm by the members of the Community.

6. That previously the Hindu Society and as a part of that, this Kshtriya Community were internally governed by small Samajas or Societies each with its controlling head and Panchayat or a council composed by the Pramanikas or persons of proved virtues and good trust; while all these small societies formed parts confederated and combined by love and authority of a higher organisation which ordinarily was the state with the Raja or king at its head. These Samajas were in their respective spheres self-governing and representative, and worked by love with the view to the common local, blending the people as if in one body, making them respect the order and law and guiding to their higher destinies. Their leaders as also the king himself were completely under the control of the law and order. And the reverence for the good and beautiful, the love to all and respect and obedience to superiors as also to the law and order made them loving confederates with all other similar Samajas as also the rest of mankind. Even in matters of interest partly temporal, a well-working and representative system of administration can be found in the Dalai system of the administration of the holy Kamakshya Temple and the connected Estates. There, too, the principles of reverence, love, respect and obedience are at the base.

7. That owing to disregards more or less to the self-governing and self-improving institutions and as an effect of the present system of education, the finer elements are gradually disappearing and in their places self-interests even of somewhat baser kind are gradually gaining ground bringing in its train even discontentment and disrespect for the law and order.

8. That to get things all right and to bring about the desired reverence, respect, love and obedience to law and order, of course consistently with the respect for self which keeps a man firm and virtuous, makes him do what is good in life, most well-intentioned judicious and substantial help at the hands of the protecting powers is necessary and it will be a very great thing if the protecting power the King-Emperor be pleased to grant us that most judicious help, so that all the people of India and for the matter of that, all the people of the British Empire can live in peace, prosperity and mutual love and respect.

9. That what is that most judicious help and how that can be administered are questions which can be fitly grappled by persons who are most conversant with the whole human nature and the whole affairs of the Empire, But in view of the situation, I on behalf of the Kshatriya Community, beg to make the following humble submissions:-

(a) That the Government should retain the power to render requisite help to the different communities according to their needs and aspirations and to place them all such a good position that there may be mutual love, respect, and help.

(b) That the self-governing and self-improving Institutions are not in any way impaired but encouraged without any interference to their principles and works to work out their self development.

(c) That in the matters of municipal, village Communities and Panchayats be established and recognised as units and made the basis of popular representation.

(d) That if representations of the people in the councils of Government is wanted, the representation must be thorough and every community high or low, and every interest should be allowed to be represented by members of their own community and not by men who belong to other community as they may not have identical views and feelings on any subject.

(e) That care should be taken to secure the due consideration by the Government of the interests of the small communities or interests sending one or few representatives. For these representative may be easily outvoted by others who not being identical in thoughts and feelings may not find their hearts in accord with that of the few representatives, and guided by their own view of things may go and by their volume of speech may lead others to go against the most cherished object of the community represented by the solitary members and thus establish a rule of one part of the people over the other.

(1) That the system of education be no modified that every community may develop its own religious, social and moral ideas and that impetus be given to the industrial education and enterprise. I have the honour to be

Dated, Rangpur

The 5th November, 1917

Sir,

Your most obedient servant

Panchanan Barma

Secretary, Kshatriya Samiti.

Below telegraph had been sent as reply letter –

Panchanan Barma

Secretary, Kshatriya Samiti,

Rangpur, 3-12-17.

Your letter of 6th November has been printed and placed before viceroy, Secretary of State, regret impossible arrange for personal interview,

P.S.G."

Other proposals of the Kshatriya Samiti during first meeting were-

Establishment of treasury

A total of Rs. 960 was collected in the first meeting itself.

Hostel setup: A student hostel was built at the expense of Rs 14700/, with the accommodation of 32 students.(This meeting was sponsored by Mahamahopadhyay Shri Yadaveshwar Tarkaratna Mahasaya.)

Upanayan

First Upanayan arranged on the banks of Karatoya river at Debiganj of Jalpaiguri district. It was meeting place of Kshatriya people. On 27th of Magh, the Upanayan ceremony was presided over by the famous Brahman Pandits of Kamrup, Mithila and Navadwip. Panchanan Barma, secretary of that programme received alms from his mother Champala Devi.

Rangpur College and Kshatriya Samiti

Mr. J.N. Gupta, ICS, District Magistrate asked for Rs. 25000 to establish Rangpur college but Rajbanshi kshatriyas from other districts did not cooperate, so it was remained unsuccessful.was remained unsuccessful.

German battle and Kshatriya troop

Around 400-450 Rajbanshis from undivided Goalpara district joined in battle in 1322 (Bengali year). Chief of army from Karachi wrote to Panchanan Barma –

“The men of this Kshatriya community make better soldiers than the others.”

Sahitya Seva

Thakur Panchanan Barma’s contribution was enough for the Bengali literature. Shri Surendra Chandra Roy Chowdhury established the “North Bengal Literary Council” in association with Thakur Panchanan Burma. “Chhilka” worked tirelessly to rescue and propagate what was written in the vernacular of the independent state of Kamrup or Cooch Behar.

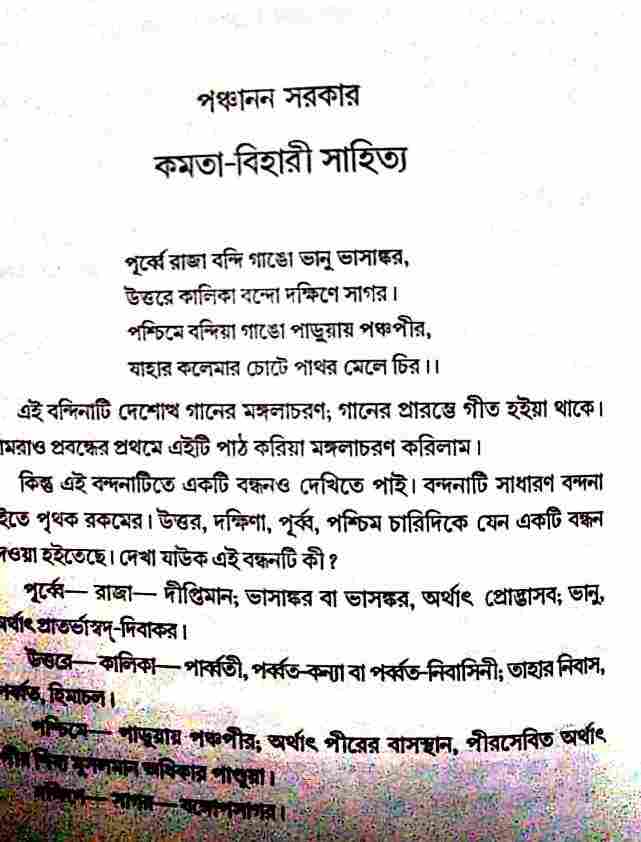

“Naadim Poramaniker Patha” and “Jagannathi Bilai” wrote by Rai Saheb Panchanan Barma. It was an example of pure Kamtabihari or Kamtapuri literature.

“Kamatabihari Sahitya” another writing penned by Thakur Panchanan himself.

Kshatriya Patrika

TThe uneducated Kshatriya community does not keep abreast of the conventional newspapers. Panchanan Barma started a monthly magazine called “Kshatriya” for Rajbanshi people.

Kshatriya Bank

At the general meeting of 1320 (Bengali year), Raisaheb Panchanan Barma proposed to establish a bank to help the Kshatriya community move forward economically. The jotedarsand prosperous farmers of the Rajbanshi community raised a common fund so that it to be spent for the general welfare of the community. They set up a financial organisation, known as “Barma Company”, located at Ganibandha of Rangpur district. The basic objects of the company were to provide loans to the poor to protect against the landlord and moneylenders. They urged the cultivators to improve their agricultural practices and called upon them to organize co-operative credit societies.

The bank was not established in Rangpur town as there were no active Kshatriyas who could lead. But in 1327, Kshetranath Singh came from Kurigram to Rangpur to practice law. In fact, Kshatriya Bank was established on his initiative.

Library

As soon as the scriptures were published, Panchanan Barma felt the need for a library and set up a small library with noble gesture.

Expel from Coochbehar State (1926 AD)

An unexpected event took place in 1926 apart from the non-cooperation of the Cooch Behar state towards the Kshatriya movement. It was a great shock not only for life of Panchanan Barma but also the history of the Rajbanshis. Panchanan Barma was expelled from the state of Cooch Behar by a notice of 24 hours. It is further ordered, Panchanan is prohibited to enter Coochbehar state for a period of 5 years from the date of this order is communicated to him without any special permission, previously obtained of the Regency Council. The banished order was as follows:-

Notification regarding Raisaheb Panchanan Barma

And whereas the Council consider it necessary in the interest of the state ,that the Rai Saheb Panchanan Barma should be prevented from carrying on a mischievous propaganda in the State and also to mark their displeasure at his disloyal and scandalous conduct in getting up the forged petition referred to above and utilizing in a manner calculated to bring Her Highness the Maharani Regent and the Regency Administration generally into contempt with the subjects of the state and the public generally and to create discontent in the State against Her Highness the Maharani Regent and the Regency Administration generally.

It is hereby ordered that the said Rai Saheb Panchanan Barma is prohibited from entering the State for a period of five years from the date this order is communicated to him without the special permission, previously obtained of the Regency Council. It is further ordered that ,if at any time the Rai Saheb Panchanan Barma enters into any part of the State in disobedience of this order, he will be liable to be arrested by the Police and removed from the State and that he shall also be liable to prosecution on connection, to be punished with simple imprisonment ; for a term which may extend to three months or with fine which may extent to five hundred rupees or with both provided that no such prosecution will be undertaken except with the sanction of the Regency Council.

By order

Sitesh Chandra Sanyal

Registrar, Regency Council

Cooch Behar.

The historical analyst of Panchanan Barma have given so many explanations to this issue, Sri Upendra Nath Barman writes that Panchanan had great honour for women and had openly Protest against its disrespect for which he was banished from the State for five years. Shri Dharma Narayan Bhakti Shastri Sarkar has also mentioned that the reason for which Panchanan Barma was punished is unknown still today. Rai Saheb Panchanan has never expressed the reason personally and he did not prefer to mention it. Panchanan Barma’s daughter in law Hemlata Devi, the wife of his only son Pushpajit Barma said in an interview that Panchanan had commented about the character of Maharani Indira Devi of Cooch Behar for which he was banished from the state.

Last Breath of Panchanan Barma

Raisaheb Panchanan Barma had suffered a lot due to family issues many years before his last life & death. He could not maintain any discipline in the world for being expelled from the state of Cooch Behar for 5 years in injustice. His only son Mr. Pushpajit Barman tried hard but not being able to pass B.A., which was a cause of pain for Panchanan Barma. Raisaheb Panchanan was of moderate character with great patience. His character became more pleasant due to his generosity and nobility. Panchanan Barma was a fearless and outspoken speaker. He loved the Kshatriya Samiti whole heartedly and thought round the clock how to improve the society. During the arrangement of the annual session of the society at Jalpaiguri in 1935 AD, he went from village to village to collect money and became sick due to overwork. Shortly after the end of the session, he fell seriously ill and was admitted to Calcutta Medical College for treatment. But despite the efforts of doctors and the sincere care of others, anemia and paralysis continue to worsen. Raisaheb Panchanan Barma died at Medical College hospital on September 9, 1935, after suffering for about 20-22 days. Many mourning meetings were held in Calcutta and various districts on the occasion of his death.

Post Panchanan Barma and Kshatriya Samiti

Tebhaga Movement and Kshatriya Samiti

Kailu Barman of Gaya Bari had ryotwari rights over three acres of land in 1929. At the time of the economic crisis in that year he sold this land to the jotdar and became a contract tenant under him.

During the 1943 famine he sold his contract tenancy rights and became a share-cropper. Then in 1946, reduced to starvation level he sold his plough and bullocks and became a landless agricultural labourer. Kailu Barman was a share-cropper of Nilphamari sub-division [Reference: Collected from Thesis/Book by Swaraj Basu]

Now question is what was role of Kshatriya Samiti or samitis?

[Kailu Barman was also Koch Rajbanshi or Rajbanshi Khatriya individual ]

The agitation of the poor Koch Rajbansi farmers or peasants against jotdars and the excess levies/taxes charged in hats in the late 1930s and the early 1940s was a clear indication of the differentiation within the community. Among the agrarian population of North Bengal, the Koch Rajbansis occupied a predominant position and the majority of them were adhiars and agricultural labourers. Some of the koch Rajbanshis were also zamindars and jotedars. But since the early 20th century a substantial amount of the Kochrajbanshi lands had been transferred to the non-Rajbanshi immigrants (mainly came from present day Bangladesh districts or sub districts) and many of the earlier jotedars had turned into chukanidars and adhiars. The jotdars or adhiaris who generally stayed in villages with their share croppers, enjoyed life styles and cultural practices which were not very different from those of their share croppers, majority of whom belonged to the same community. However, this situation began to change from the late 19th century as a result of migration of non-Rajbansi settlers into the Kochrajbansi lands, which changed jotedars attitudes.

The first initiative to mobilize the peasants for their economic rights was taken by the Bengal Communists with the formation of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Party in the 1920s. But it concentrated more on the worker’s front and achieved nothing to mobilize the peasantry. The party itself became non-functional after 1929. In the same period Fazlul Huq, a leading figure in Bengal politics at that time, organized the Krishak Proja Party which had the majority of its followers among the Muslim peasantry. But it represented the interests of substantial tenants and rich peasants and its main objective was to dominate the local and District Boards, depending on the support of the Muslim peasants. Its real influence was in the districts of Tippera, Noakhali, Dacca, Pabna, Bogura and Mymensingh, though it was also active in Rangpur, Dinajpur, Bakarganj, and Murshidabad.

The government’s assessment of the peasant movements in the year 1935 was as follows:- “Although from time to time attempts have been made by Congress workers and Communist agents to organize associations (peasants) on a wider political basis, little real progress has been achieved in this direction”. [Ref. Book Dynamics of Caste Movement. By Swaraj Basu]

From 1936 the situation began to change. After the establishment of the All India Kisan Sabha, its Bengal provincial branch was set up in 1936. The leadership came mainly from the non-cultivating middle class, as well as from some of the middle peasants at the local level. But it gradually became more identified with the interests of the poor peasants and polarization of the Bengal agrarian classes into different political parties was clear by 1940. What is important about this period was the attempt made by the ex-terrorists (Naxals) and Communist Party workers to rally the poor peasants against the landlord’s exploitation.

It was reported to the government in 1938 that a disturbing development took place in rural areas and this may best be described as the growth of a “no rent mentality”. Congress and other revolutionary elements were active in encouraging tenants to withhold the payment of rent, in promoting hatred to landlords, in organising opposition to canal dues and local rates. This was an indication of the growing discontent among the peasantry in the late 1930s. In 1938, the district Krishak Samitis were formed at Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri and Rangpur, and these were instrumental in organising share-cropper’s struggle in north Bengal during 1939-1941.

By the end of 1939, in the Boda, Debiganj and Panchagarh thanas of Jalpaiguri, the share-cropper’s movement first started by ‘involving large sections of Koch Rajbansi and Muslim peasants and adhiars. It was the excessive tolls at hats, various levies imposed on adhiars and the high rate of interest on grain loan which agitated the share-croppers. The adhiar’s major demand was to take the harvested crop to their own threshing place. In Dinajpur the major centre of movement was Thakurgaon subdivision and the sharecropper’s grievances were also the same.

The agitation had initially started against excessive taxes at haats (village markets) and melas (village fares) which the peasants had to pay. The most famous were the movements at Kalir Mela and Alokjaoar Mela. Very soon the adhiars demanded relief from all excessive illegal cesses and reduction in the rate of interests. They also refused to pay the Union Board taxes. The movement took violent turn in many areas and the adhiars suffered a lot at the hands of the police and the jotdar’s lathials. Similarly in Rangpur the haattola movement spread in different local hats and Krishak Samiti volunteers mobilized the adhiars against the atrocities of the jotedars.

The nature of the movement remained the same, mainly confined to asking for relief from the excess demands of the jotedars. In the same period the government’s scheme of restricting jute cultivation created resentment among the adhiars in Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri and Rangpur. The jotedars kept in their possession the specified lands for jute cultivation and thus deprived the adhiars of the benefits of producing jute. The provincial reports on the political situation during 1939-1941 reveal the growing concern in the official circles about the militant mood of the adhiars. The latter could not however sustain their struggle for long, and it was ruthlessly suppressed by joint repression of the state machinery and the jotedars. But their agitation had certainly forced the latter to concede some of their demands.

The most significant about this movement was the participation of a large number of Koch Rajbanshi adhiars. The Kshatriya Samiti which was actually dominated by the Rajbanshi jotdars and substantial peasants viewed this movement as a conspiracy of upper caste leaders and kept itself away from the share-cropper’s struggle. In its annual conference held at Gaibandha in the district of Rangpur in August 1941, the Samiti passed its usual resolutions for the improvement of the social, educational and economic status of the Rajbansi kshatriya community. This conference was chaired by Shyama Prasad Barman who was their representative from Dinajpur in the Bengal Legislative Assembly.

A totally unconcerned Kshatriya Samiti registered its disapproval of the whole agitation. But this could not stop the Rajbanshi adhiars from the movement, and here lay its special significance. It was showed that the jotdar and adhiar clash or conflict was never faded or deflected by caste or religious divisions, despite attempts to do so by sections of the jotedars and by other organized political organisations.

Historian Sugata Bose mentioned that – The Rajbanshi Kshatriya movement proved of no avail, to prevent conflict between adhiars and jotdars of same community. The memoirs of the activists in this movement as well as government reports on the political situation of the period bear testimony to the participation of a large number of Rajbanshi adhiars, small jotedars and women in the sharecropper’s movement of 1939-41.62 Caste, religious and ethnic identities thus merged into class identity.

The Rajbanshi, Santal or Muslim adhiars all participated in the same share-croppers’ struggle as one collective body. The share-croppers’ movement of 1939-41 seemed to be the dress rehearsal for a major showdown between the ahdiars and the jotedars in 1946-47. The lessons of 1939-41 movement helped the Communists to understand better the agrarian problems and the nature of class conflict in the countryside.

The Communist workers were also trying to regain their base among the masses which had been lost because of their pro-war policy. So in 1946, the initiative for the movement came first from the Communist workers. As the S.D.O., Sadar Sub-division of Dinajpur reported, ‘The movement started early in December 1946 when some workers of the Communist party of this district and some local workers of Kisan Samitis (all prominent adhiars) started inciting the adhiars asking them to remove all the paddy home after harvesting, instead of taking them to the jotedar’s kholan (place near home where crops are collected) as in the previous years’.

The call for ‘Tebhaga’ or two thirds share of the produced crop was subsequently given by the Bengal Provincial Kisan Sabha m September 1946. But whatever might have been the role of the outside leadership in this movement, it is hardly possible to overlook the fact that it was the jotedars’ growing depredation which had pushed the adhiars into the path of rebellion. Their condition is best depicted by a contemporary Kisan Sabha activist of Rangpur.

Such was the picture of increasing indebtedness and pauperization of the rural peasantry in north Bengal. Simmering discontent of the peasantry therefore at the slightest provocation had burst forth into open rebellion against the jotedars. The question is not where it started first and who started it – from December 1946 to mid-1947 it was adhiars who dominated the movement throughout the countryside. In Dinajpur – the Sadar, Balurghat, and Thakurgaon subdivisions, in Rangpur – Nilphamari, in Jalpaiguri – the Sadar subdivision were main affected areas during the Tebhaga movement.67 The major demand of the adhiars was to carry the paddy to their own threshing-floor and two-thirds of the crop was to be their share. The most popular slogans were, ‘Nil Khamare Phan Tolo’ (put the paddy in your granary), ‘Adhi Nai, Tebhaga Chai’ (not the half, but three-fourth share we need), ‘Jan Debo Tobu Phan Debo Na’ (we will give up our lives, but not the paddy)

This, in short, is the story of the Tebhaga movement in north Bengal. The Kshatriya Samiti’s call for caste solidarity was no doubt a major factor that detracted the attention of the Rajbansi adhiars and the poor peasants away from the share-croppers’ struggles. Using the caste sentiment, the Rajbansi leaders tried to dissuade the poor peasants from participation in the anti-jotedar movement which was bound to go against the interests of the Rajbansi jotedars. But in the long run they do not appear to have achieved any great success in this direction. Apart from some vague sympathy for the poor within the community there was no positive initiative on the part of the caste leaders to take up the cause of the Rajbansi adhiars: This perhaps explains why the latter disobeying the commands of their caste elders took part in the agitation. [As per Dr. Swaraj Basu’s book]

Somnath Hore’s Tebhaga Diary – A narrative, dated 27 December 1946, revealing fighting spirit of the struggling adhiars:-

I sketched some of the leaders of the sharecroppers’ movement of 1940 this morning. The sixty-five year old “Mamu” Ramprasad Barman, was an enthusiastic activist in that movement. His enthusiasm remains as strong as ever. This afternoon he set out for the village market at Khaga, lathi in hand, to join in the demonstration against the landlords and their oppression. I said, “you are an elderly man. If the thugs attack you, do you think you will be able to defend yourself with that lathi”? He answered, “well, even if I cannot break their bones, I can give them a few bruises, can’t I”? When I asked whether he felt tebhaga would be a success he said, “I have fought in the past, I am fighting now, and I will fight in the future. If we keep up the struggle we are bound to succeed.

Government’s eye on Rai Saheb

State Government

Like Vir Chila Ray, the great koch warrior of Kamtapur state Rai Saheb Panchanan Barma also remained deprived long time from Kolkata oriented West Bengal government. Congress government did not do anything regarding enlisted Panchanan’s biography in school text books. Communists were against caste politics or we can say they were against koch Rajbanshi Kamtpur from language movement point of view or social point of view. Present government did something like establishment of Coochbehar Panchanan Barma university and its 2nd campus at Khalisamari, birth place of Thakur Panchanan. But again the same thing what a Koch Rajbanshi keep in mind, that is the name of university. We usually tell Vidyasagar university or Rabindra Bharati University. West Bengal government did not recognise that university as name like “Kolkata Rabindra Bharati University” or “Kolkata Vidyasagar University” or something like “Bankura Rabindra Nath Tagore University”. I don’t know whether it was Panchanan’s felicitation or Panchanan’s humiliation by treating as 2nd or 3rd class legend. People never fight or do movement for set up a murti or idol of Rabidra Nath Tagore throughout West Bengal but here at Kamta region, kamtapuri Koch Rajbanshi people always carry movement for establishment of their legends.

Central Government

Till date no government (central) had done anything either for Vir Chila Ray or Rai Saheb Panchanan Barma. But i think its fault of Koch Rajbanshi Kamtapuri leaders and voters who caste their vote (since 75 years of Independence) for such faulty leaders. Nobody is trying to unite the entire kamta (Koch Rajbanshi) society.